What a Single Audit* Means for Your Organization

- Contributor

- Gwen Mansfield-Vogt

Dec 1, 2021

The single audit* is an assurance* tool commonly used to hold recipients of federal funds accountable for how those funds are spent. Following the influx of federal COVID-19 relief funds, more entities than ever are subject to the single audit. For example:

- Smaller nonprofits, especially those that serve populations most impacted by the pandemic, such as children, the elderly, and the homeless.

- Smaller state, local, territorial, and tribal governments.

- Many proprietary and for-profit K-12 schools, as well as colleges and universities.

- Hospitals, nursing homes, and many other healthcare providers that received money from the Provider Relief Fund.

- Movie theaters and other shuttered venues.

To be an effective steward, you need to understand the purpose of the single audit, know what and when you are required to report, and realize what’s at risk if you don’t comply.

What Is a Single Audit?

A single audit includes both an audit of the organization’s financial statements and an audit of the organization’s expenditures of federal award money. As part of the public record for nonprofits and governmental entities, this type of audit provides assurance that the non-federal entity implements adequate internal controls and complies with program rules.

The single audit requirement kicks in when a non-federal entity expends $750,000 or more in federal funds in one year. Pay close attention to the cumulative total received, because that threshold applies whether the funds come from one grant or a combination of several smaller awards.

Is My Organization Subject to the Single Audit?

Determining whether an organization is subject to the single audit isn’t always straightforward. If it spent federal funds of more than $750,000 in a single fiscal year, then the requirement generally applies, even if those funds came from multiple sources. (Funds from the Paycheck Protection Program, however, are not subject to the single audit.)

Being a subrecipient of funds from another nonprofit or governmental entity can trigger the single audit requirement, but not always. The contract or grant may state that the organization is a beneficiary rather than a subrecipient of federal funds. This distinction is important, as it exempts the beneficiary organization from the single audit requirement.

How and What to Report

Emergency funds went out unexpectedly to many entities that have never before been subject to an audit, leaving many organizations unaware that they must report on those expenditures to keep the money. If you are unsure, check with the agency or entity that made the award or sub-award. The contract or grant will specify what must be reported, when, and how.

All entities that received federal funds should be sure to keep clear records documenting:

- Program-related expenditures and revenue shortfalls. Include receipts, invoices, payroll records, and other documentation tracking spending and revenue.

- Evidence of internal controls. Maintain paper or electronic documentation of review and approval that can be verified by an auditor. For example, can you show that someone reviewed the report before it was submitted to the awarding entity?

- Procurement policies. Be sure to include evidence of soliciting bids or quotes from multiple qualified vendors and checking vendors against the System for Award Management database to see if they are barred from federal awards. If the funding was needed for emergency purposes or went toward a qualifying sole-source purchase, maintain documentation to support why the organization chose the vendor. For example, a hospital that needed more ventilators for COVID patients would not have to solicit multiple bids.

Keep all documentation for federal programs organized and easily accessible so you’ll be ready to give the auditors what they need when they come looking for it. That includes making sure the people who run specific programs are available (i.e., not on vacation) and ready to provide the necessary documentation.

Bear in mind that certain types of COVID-related funding (such as the Provider Relief Fund and Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds) can be used to make up for revenue shortages caused by the pandemic, as well as to cover expenses that are directly related to the pandemic. There are several allowable methods for calculating those shortages.

What’s at Stake?

There’s a lot at stake for entities that are subject to a single audit, so it’s important to have your ducks in a row. In extreme cases, the awarding agency could demand repayment if you can’t show that you used the money correctly.

Give the audit the priority it deserves — even if the auditors are not sitting in your offices. Leaders and staff alike should give the audit process adequate care and attention to avoid confusion that could create unnecessary problems. You don’t want to overlook documentation that is actually available, which could lead to a finding that the organization doesn’t deserve.

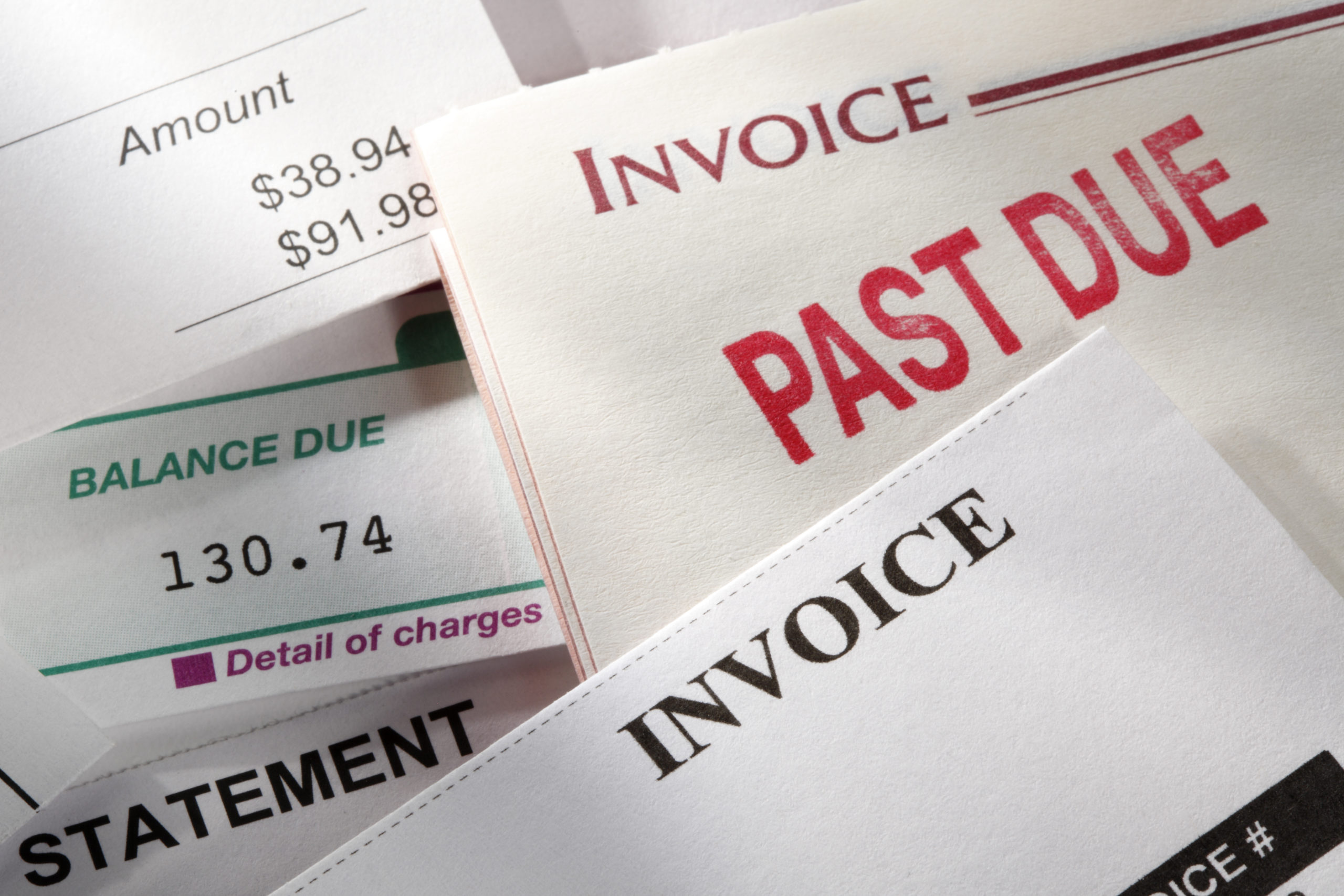

Don’t Put It Off

Timeliness is another key factor for the single audit. Late audits can result in loss of the “low-risk auditee” status, which means your single audit will cover more of your operations in the future. In some states (such as New Mexico), a past-due audit is an automatic audit finding.

Healthcare providers that received funding from the Provider Relief Fund should begin reporting through the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) portal immediately if they have not already done so. Reporting was due September 30 for the first tranches of funding, although HRSA is allowing a 60-day grace period.

If you aren’t sure yet whether you are going to need a single audit, schedule a consultation with your accounting firm immediately. Single audits are usually due nine months after your year-end, but the Office of Management and Budget has delayed certain single audit due dates by six months. These delays are creating bottlenecks for auditors, so reach out to your audit team as soon as possible and schedule the single audit in plenty of time to meet your compliance responsibilities.

Remember: Your auditors want your audit to go smoothly as much as you do. Clear and open communication is the best way to accomplish that. If you have a problem (such as lack of internal controls), let the auditors know upfront. They will be better able to work with you than if it’s a surprise.

For help determining your audit needs or preparing for your single audit, contact your CRI assurance team.